"Films for the curious" is the motto of Ironweed, a movie club that offers a monthly DVD selection to subscribers around the United States and Canada. The concept of a film club is not new in the United States, but Ironweed doesn't feature Hollywood blockbusters. Instead, it chooses films that encourage Americans to learn more about important social issues, mostly in other parts of the world.

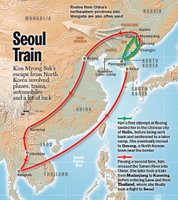

Take, for example, Ironweed's featured film last February, Seoul Train. The title refers to the Underground Railroad, a secretive19th century network in the United States that smuggled slaves from the South to freedom in the North. Only, in this documentary, the Underground Railroad is the path of North Koreans who want to flee their country, to the south.

Over scenes of police bursting into refugee hiding places and trying to prevent their escape, activist Tim Peters says, "When you come face to face with the realities of what the refugees have to tell us, suddenly, that two million dead or three million dead in North Korea starts to penetrate to your heart and your conscience, and you realize that you have to do something."

The introduction to Seoul Train is given by U.S. Senator Sam Brownback, an outspoken champion of human rights around the world, who tells viewers, "Yes, we're concerned about nuclear weapons in North Korea and what it means to the rest of the world. But the North Korean people need us, advocating for them and their human rights."

Senator Brownback quotes a Biblical verse that urged believers to feel, themselves, the chains of those who are bound. He says, in the same way, he wants the audience to not only feel empathy with North Korean refugees, but also be inspired to take action. "Please," he says, "join in the cause. Advocate for the freedom of those who do not know freedom, whose chains continue to bind them today."

[Excerpts from an article by Stephanie Ho, Voice of America]